The Rambam

You may have noticed that my family name is Rambam. When my family came to America through Ellis Island, our name was Rambam. For generations, my family name has been Rambam. I thought for once, with this new website, I’d include some background on the famous lineage of my last name.

Moshe ben Maimon was born in 1138 or late 1137. “Maimonides” is the Greek translation of “Moses, son of Maimon,”. The acronym Rambam (רמבּ״ם) is the Hebrew name.

The Rambam grew up in Córdoba, in what is now southern Spain. When he was ten, a fundamentalist Berber tribe called the Almohads took over Córdoba and gave the Jewish residents, which included Rambam’s family, three choices: conversion, exile, or death. Rambam’s family chose exile. They left Córdoba, and for the next ten years, they traveled across Spain looking for a safe place to live.

It never happened, and they eventually left Spain for good in 1160 and settled in Morocco, a North African country bordering the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. There was still religious persecution here, but Rambam and his family could practice religion at home. It is believed at this time that Maimonides outwardly practiced Islam, not out of belief but to protect himself and his family. He continued to practice Judaism in secret, and in 1165, the Rambam and his family left on a journey for Israel (Palestine).

Rambam’s lifelong goal was to bring the teachings of the Torah to all people. Not just the scholars and elite. While he was in his early 20s, he started his formal efforts to achieve this goal. In 1168, after seven years, he completed his commentary on the Mishneh, Peirush HaMishnayos.

The Rambam spent his entire life under religious persecution, and he and his family lived in constant turmoil and upheaval. Somehow, despite his dangerous environments, he created a body of work that made him one of the most influential Jewish thinkers ever.

The Rambam is also the only philosopher of the Middle Ages, and possibly of all time, to earn the respect and admiration of four cultures: Greco-Roman, Arab, Jewish, and Western.

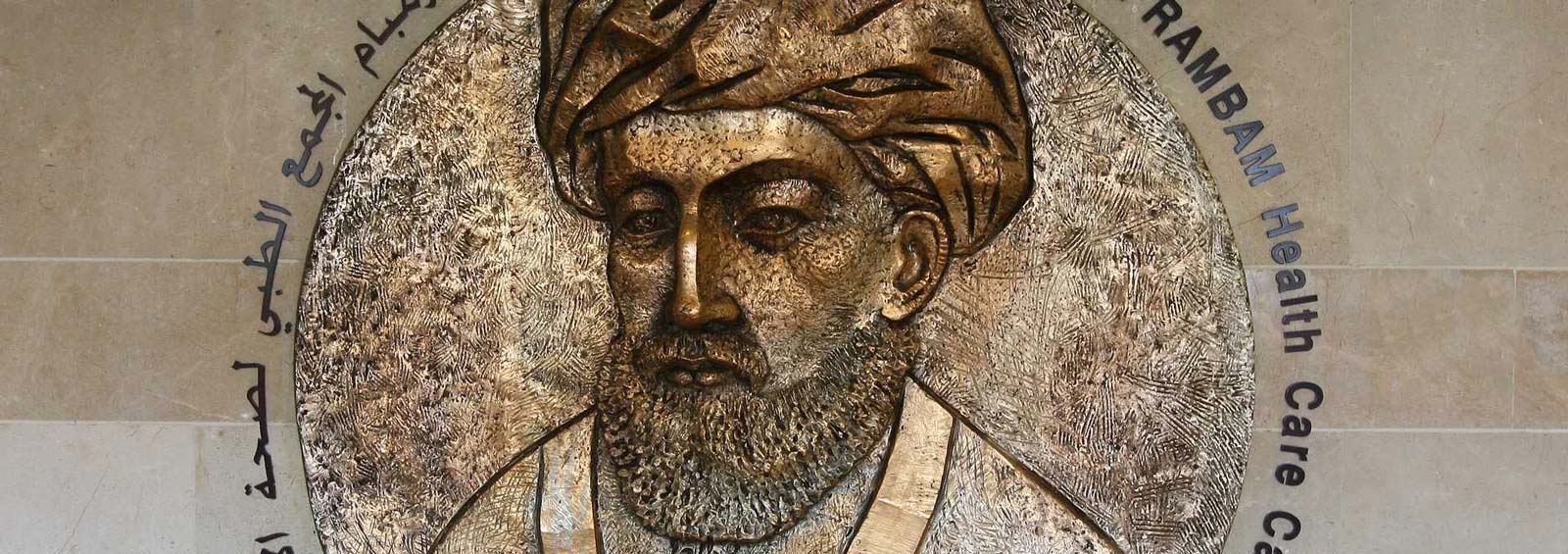

He also studied secular subjects like astronomy, medicine, mathematics, and philosophy. As a physician, Rambam was the first in Western society to propose that the health of the body and soul should be combined. He was an innovator in Jewish Law, Philosophy, and Medicine. Some of Rambam’s medical innovations are still relevant to hospitals and physicians today.

He insisted that one must care for a person’s mental health to prevent physical illness. Despite long days caring for patients, Rambam wrote extensively about medicine and philosophy. His medical works focus on several clinical topics and reflect rational medical thinking and understanding of the importance of the relationship between mind and body.

He was also very interested in Greek philosophers Aristotle and Plotinus. Blessed with an incredible memory for every detail and an insatiable intellectual curiosity, Maimonides adopted an expansive view of wisdom, which supported his efforts to bring religion to everyone. He was a true man of the people; he believed that we should “listen to the truth, whoever may have said it.”

He worked with a Muslim philosopher, Averroes, who shared Rambam’s interest in Aristotelian thought and how it coexisted with Islam and Judaism. Together, their writings introduced the followers of all three religions to the Greek masters, which helped put the foundation in place for the European Renaissance that would happen long after Rambam’s passing.

Based on the incredible number of texts that Rambam wrote, his intellectual influence on Islamic and Christian thought still exists today. The Twelfth Century was such a violent and turbulent time, which made his accomplishments and the reach and impact of his work even more amazing.

Rambam is best known for his philosophical writings and his work to bring religious thought and understanding to all Jewish people. He codified Jewish Law and revolutionized Jewish thinking with the Mishneh Torah and The Guide for the Perplexed. He wrote the two works at different times and for different audiences. Even though the two works are separate, they project a unified and reason-based vision of the purpose of Jewish life.

Rambam did make it to Israel. Unfortunately, at the time, Israel was under Crusader rule, and after a short visit, he and his family left and settled in Egypt in 1166. He would spend the rest of his life in Egypt, first in Alexandria and then in Fustat, Egypt’s first capital under Muslim rule. Rambam lived in Fustat until he died in 1204.

Rambam is buried in Tiberias, in Northern Israel. You immediately understand how essential his writings and teachings are when you read the inscription on his tombstone. “From Moses [of the Torah] to Moses [Rambam], there was none like Moses.”

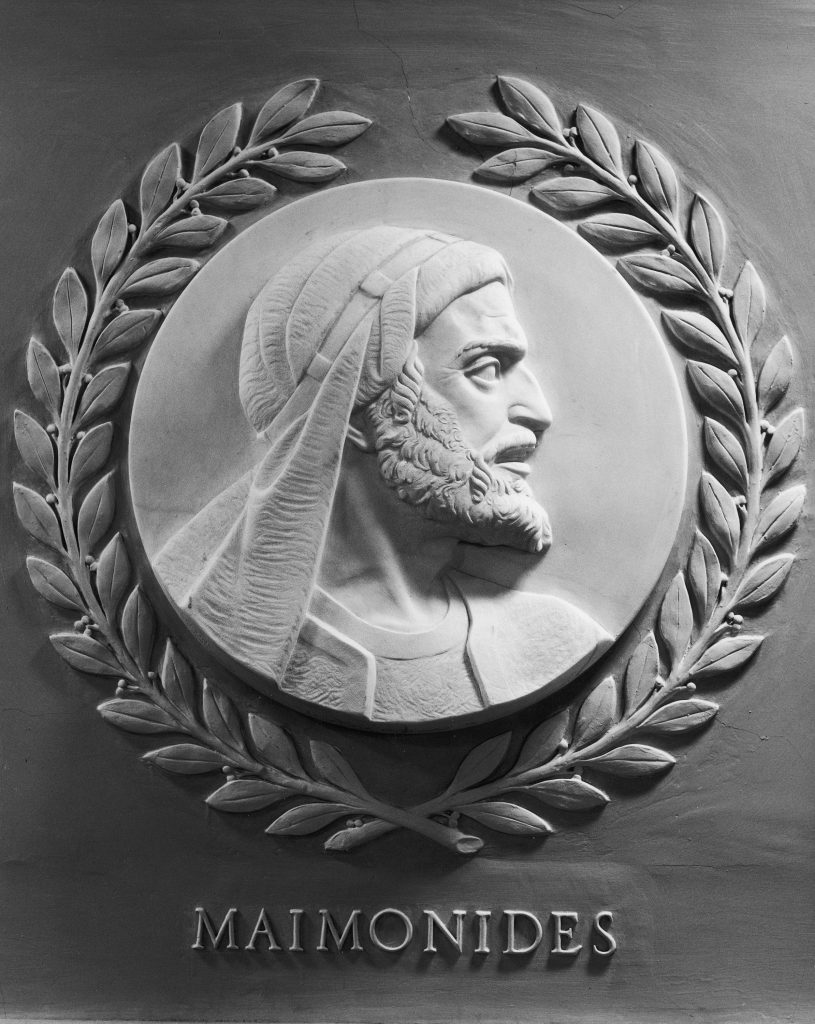

Even in America, 800 years after his death, Rambam’s impact is felt. The United States House of Representatives Chamber has 23 relief portraits.

They are “the faces of lawgivers” from across history. US Scholars, legislators, and the staff of the Library of Congress put the list together in 1949 when the capital was remodeled. Rambam was included as one of the 23 individuals “noted for their work establishing the principles that underlie American law.”

With everything happening today, Rambam’s contribution to “the principles that underlie American law” is especially important to me. Rambam states in his work that “human dignity must be weighted heavily among the factors in any crisis decision.”

He believed human dignity should override even divinely inspired legislation, decrees, and laws. Rambam’s writings set important precedents for upholding principles of the rule of law and limited government that respect human rights.

If I’ve inspired you to learn more about Rambam, there is no shortage of books, websites, and podcasts about him.

- There is also an exhibit right now through December 31, 2023, in New York. It's called The Golden Path, Maimonides across eight centuries. https://www.yu.edu/golden-path

- Halbertal, Moshe, trans. Joel A. Linsider. Maimonides: Life and Thought. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2014.

- Kraemer, Joel L. Maimonides: The Life and World of One of Civilization’s Greatest Minds. New York: Doubleday, 2008.

- Maimonides, Moses ( Isadore Twersky, ed.) A Maimonides Reader. New York: Behrman House, 1972.

- Stroumsa, Sarah. Maimonides in His World: Portrait of a Mediterranean Thinker. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2009.

- Maimonides the Rationalist, by Herbert A. Davidson, The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization.

- Maimonides – by Kenneth Seeskin for Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Maimonides (1138—1204) – by Jonathan Jacobs for the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Maimonides (Rambam) and His Texts – by Danny Moss for My Jewish Learning website.

- Moses Maimonides | Jewish Philosopher, Scholar, and Physician – by Ben Zion Bokser for Britannica.

- Sarah Stroumsa on Maimonides – Conversation with Peter Adamson for History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps podcast.

- Sarah Stroumsa on Maimonides – Conversation with Peter Adamson for History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps podcast.

- Jewish Philosophy: Maimonides – Joe Gelonesi interviews Steven Nadler for The Philosopher’s Zone podcast.

- Maimonides – by Melvyn Bragg and his guests John Haldane, Sarah Stroumsa, and Peter Adamson for In Our Time BBC Radio 4 podcast.